We need smarter issue trackers

While issue trackers originate as tools to manage projects more effectively, during the last years of work I have been through some situations where their misuse backfired.

Tools originally conceived to improve workflows and project lifecycle became a significant burden for the team using them, occasionally making difficult situations even worse.

This post is a collection of bad patterns I have seen happening. It is not a survey of all the possible situations that can occur. It is not meant to be an argument against issue trackers (if it tells anything, it will probably be about the teams I was part of), but rather an overview of things that went wrong because of the way a particular team used those systems.

In retrospective, most of the problems were due to a lack of discipline and experience of the project teams, and they are less frequent – if present – in a team of seasoned professionals. But, while training and education can certainly help, I would love to consider a different aspect: the issue tracking systems were not helping as they could have.

Here is a summary of the most common and annoying problems I encountered

- The issue tracking system is misused

- Lots of issues are duplicates

- The system imposes over-engineered processes

- Bug reports do not include enough information

- The way priorities are managed is broken

I would love to build on top of each negative experience, with a constructive attitude, by exploring how a better designed system could induce a better behavior.

The issue tracker is misused

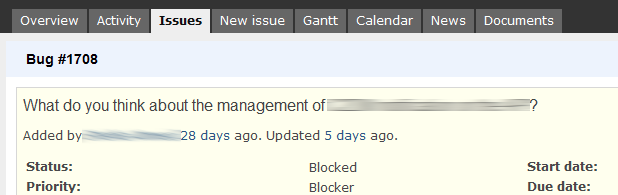

While it should be obvious that an issue tracker is a tool to track issues, they are sometimes used for other kind of communications.

The screenshot above is just the most recent example of misuse I have seen. The issues on the tracker should be items that can be acted upon, it is just not practical to use them to discuss features or to gather requirements.

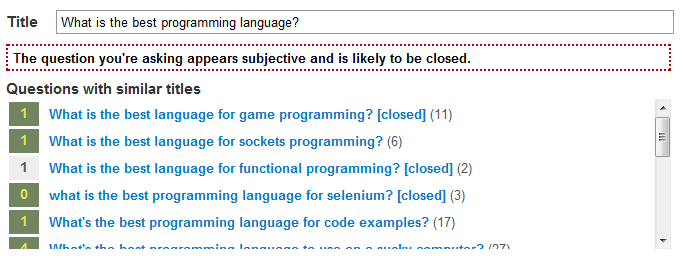

A smart issue tracker should recognize questions and conversations and warn users when they are about to post them, just like Stack Overflow does in the screenshot below.

Plenty of duplicates

Duplicate bugs are a frequent pain point for many project teams, to the extent that a frequent suggestion is penalizing testers who open too many duplicates (and this may not be a great idea, after all). While they certainly can be minimized by a disciplined team, they still are likely to occur when a large team is testing a complex software product.

Avoiding duplicates is as easy as performing a search among the existing issues, but it is time consuming, so this step is often neglected. A smart issue tracker would automatically perform this step on behalf of the user and display a warning if it finds issues that look similar enough to the one being reported. This is exactly what happens when posting a new question on Stack Overflow (and somewhat similar to what Quora does): questions that look suspiciously similar to the one entered are displayed right next to the input area.

A diligent user would realize that there’s no need to add another issue if prompted with a match, but the system would never prevent the operation from being completed: a suggestion is better than an imposition, and users should be able to make the final decision.

Over-engineered processes

Many issue tracking systems offer a very basic set of default states and properties, and allow their users to do many customizations to them from the settings page.

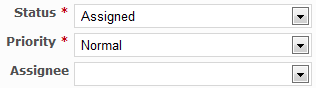

In the project I am part of, we use Redmine with a set of plugins oriented towards Agile methodologies. The default set of states and processes in Redmine has been customized to suit the project needs. Needless to say, strange things happened. All issues have an optional property “Assignee”, as expected by a system of this class. For some strange reason, however, we also have a state for issues called “Assigned”.

This redundant “Assigned” state information does not add any value to the process, it just adds one mandatory and uninformative step to the lifecycle of all issues. All the information it conveys can be derived from the presence or absence of value in the “Assignee” field. To make things worse, we can have issues in inconsistent state, with an empty “Assignee” field and state “Assigned”.

The process we ended up having for all of our tasks and issues can be simplified without loss of generality to the set of states and transitions offered by Pivotal Tracker, like the ones shown here. The only difference is that state transition in Pivotal are accomplished by clicking a button, while they are much more cumbersome in Redmine, since we need to update multiple fields at the same time.

![]()

A good issue tracker should come with a set of sensible defaults, but powerful enough to handle most situations and state transitions should be as easy as clicking a button.

Configuration should be an option, not a requirement.

Missing information

Reports without instructions about how to reproduce the bugs, screenshots of error pages, one-line reports without log extracts are frequent time-wasters.

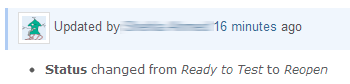

During the last few months, I have lost count of the times I have seen issues being reopened without any other information, just to discover that the test progressed but the code was breaking at some later point.

While this kind of problem is often due to inexperience, a good tracker would induce (rather than imposing) bug reporters to supply enough information. (e.g. by not allowing to reopen an issue without supplying any information)

Google Code allows project owners to specify a “new issue” template that looks like the following:

What steps will reproduce the problem?

1.

2.

3.

What is the expected output? What do you see instead?

A template is an effective way to communicate what the team needs to know in order to solve issues. It encourages users to include useful information, and makes empty reports the less natural choice (reporters have to explicitly blank out the form).

Broken priorities

The difference between the severity and the priority of a bug is often a source of confusion, even for people who have been working on issue trackers for a long time.

The severity of a bug depends on the impact it has on the underlying system, it is a functional measure, and can be estimated right when opening an issue.

The priority of a bug is a scheduling decision, depending on business requirements, time required to fix and several other factors.

Severity and priority are clearly two different concepts. Although they are correlated (high severity should generally mean high priority, but not always), they represent different concepts. For example, an issue priority can change after a rescheduling, while an issue severity can hardly change unless something changes.

There are different schools of thought about how to deal with this duality, ranging from supporting two different properties to two getting rid of one of them (e.g. FogBugz dropped “severity”).

In the last project I was working on the choice fell on the latter (we used Redmine, which supports priority by default and allows users to define custom levels). Now, while this is not a problem by itself, the highest possible issue priority configured was called “Blocker”.

At this point it should be evident about what the problem was: we were confusing scheduling with impact, automatically assuming that any issue that was blocking something else (yes, it was as vague as this) had higher priority than anything else.

To make things worse, we were using Redmine to track also our user stories and the features to be developed. What would a “blocker” priority mean, in that setting?

The chart below shows the result of this policy: in the last two months, 1 issue over every 4 was considered blocker.

The highest priority should be considered an exception, when it becomes the norm it ceases serving its purpose. “Blocker” was no longer informative, and bugs marked as such were only marginally more important than the others, which is something I do not want to see happening again.

A significant part of the responsibility is due to the confusion between priority and severity: there is no such thing as a “blocker priority”. If it is needed to track severity, there should be an option only for bug entries (not for tasks, chores and features).

The priority of a bug is a matter of planning and should not be set at the time of its discovery. A minimal triage process would have prevented most bugs being set as “blocker” just because they were blocking some automatic test routine.

A smart issue tracker would warn users when it detects that a significant part of the issues in the system have the highest priority, ideally right when they are about to open another issue using that level.

Conclusion

As it often happens, most of the problems do not depend just on the tracking systems themselves, but are caused by the way users interact with them. As said before, training and education can help a lot in minimizing the kind of patterns mentioned before, but better designed issue trackers can go a long way in reducing the possibilities for misuse.

Sites and applications on the Internet are becoming more and more powerful and refined in design. It is possible to guess what users are trying to do and induce them to use the systems we design in a proper way. It is possible to make small changes that point users in the right directions, and the previous sections offer some examples from the real world.

We can do better than punishing users when they do something wrong. We can design applications that realize when users are about to do something wrong, but instead of issuing an error message and aborting the action, they warn them, and point them in the right direction.

We should start designing issue trackers as if we were designing any other sophisticated application on the Internet.